Movie Review: INCENDIES (2011)

The Elegance and Dread of an Equation

Nawal Marwan is dead. She is survived by her twin children Jeanne and Simon, both in their late twenties and living in Montreal. They sit before the notary Jean Lebel (Rémy Girard) who had employed Nawal (Lubna Azabal) as his secretary for years. He has always considered them all to be a part of his family. The room is still and unbearably quiet. As he reads Nawal’s final will and testament aloud, Jeanne (Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin) and Simon (Maxim Gaudette) are disturbed by their mother’s final request. She wants to be buried naked facing the ground without a headstone to identify her. Where did this self-loathing come from? Jeanne keeps her composure and listens. Simon goes berserk over how cold and insane their mother was. He will not respect her wishes.

Professionally bound to secrecy about Nawal’s mysterious past, Jean emphasizes how grave this situation is: “Childhood is a knife stuck in the back of your throat. It cannot be easily removed.” Nawal will only accept a dignified burial on the condition that Jeanne and Simon accomplish a mission to redeem her. Two sealed letters lie on the notary’s desk. One is addressed to their estranged father whom they’ve thought was dead. The other one is news, a long-lost brother who was named “Nihad of May”. Their task is to find and then deliver their letters to them. Simon refuses to participate. After some soul-searching, Jeanne sets off to discover what regrets her mother had kept silent.

We cross back and forth between the divide of Jeanne’s daunting search and Nawal’s past. It is striking how much the two women resemble one another. Their determination and resolve is matched by their ethereal, solemn beauty. Their paths are separated only by decades as Jeanne follows her mother’s footprints in Lebanon from the North to the horrors in the South. For every startling chapter that closes on Nawal’s life, Jeanne comes much closer to solving the mystery. The question of ever figuring it out turns into another one supplemented by a great reluctance akin to rolling over a rock to expose the maggots underneath.

Back in the 1970s, confined in her Christian village Der Om, Nawal is almost Jeanne’s age when she is about to run off with her Palestinian lover. She is pregnant with his child. That is until her bigoted family intervenes. Her grandmother accuses Nawal of cursing the family and her brothers are prepared to perform an honour killing. Close to giving birth, she arranges to deliver Nawal’s baby herself and give it away to an orphanage. Nawal will go to University in Palestine on the condition she never return home. One of the most excruciating moments in the film is of her grandmother tattooing the back of the screaming infant’s ankle in the shadows. Just before they are forcibly separated, Nawal promises her child before they are instantly separated that she will find him again.

Years later, right after the universities close due to the insurrection that will become the Lebanese Civil War (1975 – 1990), Nawal is bravely determined to return to the war-torn south to save her lost child. As a precaution, she wears a cross to keep her safe from the wrath of the intruding right-wing Nationalist Christian soldiers who are hellbent on slaughtering Palestinians, including children. They have images of the Virgin Mary and Child pasted to their semi-automatic weapons. From bombed-out cities and underground societies, Muslim Palestinian militants plot their attack strikes against Christian fascist leaders aligned with Israel. For Nawal, being schooled on peaceful ideologies can change a person wholly having experienced the heat of an inferno and the stink of corpses attracting flies.

Lubna Azabal gives a shattering performance that should ensure her stardom for years to come. As Nawal Marwan, she transforms radically from a helpless youth to a strong, determined woman whose courage and humanity is thoroughly tested. There are times when she is downright scary. She is very convincing aging from her early twenties to late sixties. In the suicide-bomber drama Paradise Now (2005), Azabal was exceptional in a small, but crucial role as the daughter of a revered Palestine leader whose love may influence a young Arab not to commit murder-suicide for his beliefs. She has an undeniable screen presence. Just as commanding is the beautiful Mélissa Désormeaux-Poulin as Jeanne who clearly inherited her perseverance and will to survive from her mother. So much of the film’s power relies on her being open and enduring what lies ahead and behind her.

Over the years, Villeneuve has consistently made movies where complex women drive the action to their own stories. That in itself is a worthy accomplishment most contemporary filmmakers can’t claim. He is also not one to avoid the more squeamish realities of being a woman. Denying them would be a condescension. In his breakout success Maelström (2000), a dark romantic drama narrated by a series of talking fish on the chopping block(!), the movie takes its stand introducing its young heroine Bibiane (Marie-Josée Croze) enduring an abortion. To the tune of Oliver’s Good Morning Starshine, Bibiane is all too ready to put her past behind her. Villeneuve cares about her and he dares the audience to do so too. For Incendies, the camera lingers close-up on a woman’s bloody hand clutching the calf of Nawal’s leg during childbirth.

Like Stanley Kubrick’s Full Metal Jacket, I have thought of Maelström as a near contender for Best Film in its year of release by half. The first half of Maelström is so enthralling as it follows a self-destructive woman’s downward spiral in sex, drugs, and dangerous relationships. Working without a net, Croze is riveting. Her Bibiane could stand comparison with Tilda Swinton’s Julia (2008). I have never forgotten one of Villeneuve’s many terrific visuals where a line of metal coat racks before coming into focus look for a second like fish bones. However, the second half loses its momentum for me with the introduction of a redeeming love interest. In its dark, quirky way Maelström remains essential viewing, but those first 45 minutes are a rush.

In a sea of movies where women’s roles are limited to fixtures of little consequence, it is exhilarating to watch Bibiane dig herself deeper and deeper. It is not “a negative depiction on an entire gender” as some sanctimonious PC idiots would call it. I call it liberation. Her character is truly free. It is when a character is expected to set “a good example” for the pretend-adults at home that the actor has been neutered. If Nick Nolte and Ben Stiller can have dramatic breakdowns, why not Marie-Josée Croze?

POLYTECHNIQUE (2009) Trailer

It was in Villeneuve’s utterly devastating Polytechnique (2009) based on the Montreal Massacre, the first school shooting, where he called out all forms of misogyny ranging from reducing smart women to a “girls clean house” mentality from passive-aggressive professors to gynocide, its ugliest expression. In December 1989, twenty-five-year-old Marc Lépine (tellingly, the film could only muster calling him “the killer”) targeted and murdered fourteen young women because they were learning to become engineers and that offended him.

Again, Villeneuve introduces a woman preparing a sleek facade by shaving her legs under a shower head while studying for a test. This was Valérie (Karine Vanasse) who could not foresee that today’s class would consist of being cornered and gunned down with her friends. Miraculously, she lived. Polytechnique drew definite lines between the extremes of evil, good, and those who survived still enduring that nightmare. It was just that heroism – the need to live and love having faced unblinking malice – that made me break down in tears. It made my top ten that year.

In Incendies, Maxim Gaudette has a juicy role as the intense brother Simon. His character is truly heartfelt despite the anger that overwhelms him. He also gets to say the tackiest line of dialogue, which Simon must quickly apologize for. Those brave enough to watch Polytechnique will remember Gaudette who went through hell playing that same killer, standing on tables and shooting people trying to hide under them. As an actor, Gaudette proved a force to be reckoned with – playing on the most loathsome murderers in recent Canadian history on film and portraying him with deep, pathetic conviction. His work playing Simon in Incendies is just as expert and fearless.

Rémy Girard plays the notary as a segregate father figure. He exudes both support and caution to our heroes. Casting him is a good luck charm seeing as how he played the adulterous family man dying of cancer (“I voted for Medicare and I will accept the consequences!”) in the Denys Arcand masterpiece The Barbarian Invasions (2003), which won Canada the Best Foreign Film Academy Award. Several years later after that, it looks very likely that Incendies will win the real gold for Canada again in the upcoming Oscar telecast. The film also shares similarities in tone and astonishing revelations with last year’s rightful winner from Argentina, The Secret in their Eyes (2009) by Juan José Campanella.

Villeneuve tightly directs Incendies using evocative set pieces driven by dialogue as well as channeling his use of striking (and often wonderfully surreal) visuals in much subtler ways this time. He knew he had a great story to tell and wasn’t going to leave anything to chance. At one point, he identifies a fascist leader by comparing his portrait from propaganda posters on a wall outside to his face screen printed on a shirt worn by a terrorist. His wit is in check when he informs us of danger relying only on the beeps from a metal detector. A clever transition used for a flashback at a swimming pool is a nod to a similar shot from the Powell and Pressburger film The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp (1943).

There is a scene free of dialogue that involves ferocious swimming at night followed by a disquieting embrace. It is here where the heart of the film is not only strong, but vulnerable and shaken by a brush of death from long ago. No matter how far back it was, even at a time lost to memory, there is no buffer from that immediate chill. Delusions of safety are easily shattered.

From the very first shot and onwards, Villeneuve drives the film like the captain of a ship. The first sequence is unforgettable. A vast Middle Eastern landscape looks bleak under the harsh sunlight. We hold on this image as the beginning of Radiohead’s You and Whose Army softly scratches on the soundtrack. But the shot is moving; very slowly the exterior is closed out by the edges of a stone window ledge. Young boys dressed in rags hang their heads while standing in line. They are beaten. One child has a gash that comes down his cheek like a tear from his eye. The faceless adults are hardened, militant, and carry large guns.

The Radiohead song is like a rolling bridge, taking us to a place that looks familiar on television evening reports, but is otherworldly, lost to history and very real. “Come on, come on…” Hair falls softly on little feet. Hope dies here. We close in on one orphaned child in particular as his head is being shaven to the scalp. The man’s hands are gentle. The music thunders with dark piano keys. Off-screen, the singer wails “We ride tonight! We ride tonight!” For a very long time, the child glares at us, his eyes burning beneath his brows and never blink. Don’t you dare forget about me. This scene alone is worthy of confusing as a lost reel by Martin Scorsese.

YOU AND WHOSE ARMY?

by Radiohead

LIKE SPINNING PLATES

by Radiohead

![]()

Villeneuve gets terrific mileage off of that Radiohead song when he uses it again at the transformative midpoint in Nawal’s story. The film is so reserved that Grégoire Hetzel’s moody score sounds off in about twenty ear-strained minutes. Blocks of red type as large as those in a Richard Shepard film (The Matador, 2005) stamp the entire screen – my favourite out of the ominous titles reads DU SUD (translation: The South). For those new to Radiohead, their song Like Spinning Plates could be confused as a version of the previous song played backwards. It is most appropriate as it establishes the cruel confines of the Kfar Ryat penitentiary in Deressa – stirring strange, disorienting feelings.

Incendies is the new addition to a list of compelling movies made in the last few years about the Lebanon War. They include Joseph Cedar’s Beaufort (2007) set ten years after the war ended, as well as two more that explore its beginnings such as the rotoscope animated documentary Waltz with Bashir (2008) by Ari Folman, and last year’s terrific movie-in-a-tank Lebanon (2010) by Samuel Moaz.

The film is based on the play Scorched by Lebanese-Canadian playwright Wadji Mouawad whose literary inspirations are easy to figure out for those who’ve seen it. The new title Incendies gets the same idea across, which translates as “outbreaks of fire”. It is saved for the very end of the film with an image that is haunting for reasons that will surprise first-time viewers. Sometimes an entire lifetime can be seen as a very cruel joke.

Villeneuve’s adaptation is direct and thorough. Pieces of the central mystery are revealed within his relaxed control as a storyteller. He only lets us get ahead of the story when he decides it’s time. Like a magician, he distracts us into focusing on one thing while he does another right in the open. The mystery works mainly because every current struggle towards it so compelling. He plants the seeds in the narrative carefully. Consider an introduction to a Westernized math class that Jeanne attends. The professor begins, “Welcome to the world of pure mathematics and the realm of the solitude.” As he elaborates on what is to come, it is really Villeneuve speaking to us about the narrative, the journey full of challenges and twists before us. It is a given that Villeneuve uses cinema language throughout, but he also exercises the language of math to give form to the plot.

The whole movie is absorbing. Director Denis Villeneuve spends time building up all of these scenes for us to live in them for awhile. He holds his shots. When Simon and Jeanne argue outside a barren industrial street in Montreal, he moves his camera a little to the right at first by following them out of a building and then holds the shot still. They are filmed at a far distance. No cuts. No close-ups. Nothing unnecessary. We get all the emotion and drama from back here. Due to the way this scene is filmed, we also benefit from a startling rush of adrenaline thanks to a sudden outburst by Simon. Perhaps Villeneuve thought to do this scene from his vantage point watching the play on stage.

Villeneuve is so confident that a group of characters can search and gets lost in a resident alleyway; one character asks where they are going and the other admits that he doesn’t know. Lesser filmmakers construct their scenes at great expense as hazard zones that are loudly demolished at once. For instance, look at the scene where Jeanne inquires about her mother to a gathering of women from a Middle Eastern village. Just as Nawal is identified, the room changes from amicable to sudden hostility. Villeneuve holds the moment much longer than we’re used to. We, along with Jeanne, are not privy to what is being said in Lebanese – only the French dialogue is subtitled. It is this gradual, deliberate pacing that allows us to really be in that room on edge with Jeanne before she is finally told to leave.

A Clip from INCENDIES:

The way Villeneuve economizes these characters is truly inspired. Like the return of Mr. Bandy who owns the Bandy Tract, another character comes back for urgent reasons. This leads to a very intense scene of being blindfolded and escorted with armed goons to meet a retired warlord. Incendies not only has the feel an epic novel, but its modern-day tragedy carries the power worthy of a myth. The line between good and evil is definite, yet blurred around the inner edges. These characters perform strong gestures out of hate and love for very complex reasons, or in some cases because they were misinformed.

In what is destined to be long remembered by serious filmgoers, the intense scene on a bus taken hostage by the Christian militia commits a vicious twist on the well-good convention of a survivalist’s bluff to save more lives in the face of death. It is a well-known ploy from Oscar-winning films centering on the Holocaust from Schindler’s List (1993 – “HIM!”) to the 2007 short Toy Land. Despite quick thinking on Nawal’s part, she couldn’t have expected a little girl to do what’s only natural.

At the Vancouver Internation Film Festive last year, I passed up the opportunity to catch Incendies after watching Cristi Puiu’s Aurora (2010) and Julie Bertucelli’s The Tree (2010), which coincidentally was also scored by Grégoire Hetzel. So I caught a three-hour Romanian film by the maker of The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (2005 – it could easily be improved by cutting out one half-hour from its slogging time) and I ended up missing the film that would win the festival’s Best Canadian Feature Film! Fiddle-sticks… I must admit I am actually relieved. I would have hated pitting Incendies against The Social Network, my top pick for 2010, not to mention Black Swan and The Ghost Writer.

We are truly privileged to have a film like Incendies. Watching the film a second time only made me sink deeper in my chair. My heart beat faster. There is no escape from Incendies. Now Villeneuve has without dispute secured his place as one of the most accomplished filmmakers working in Canada along with David Cronenberg, Atom Egoyan, Guy Maddin, and Denys Arcand. It’s far too early in the year to make such an audacious prediction, but if Incendies is not the best film of 2011 then I can’t wait to see what else is in store.

INCENDIES US Trailer

INCENDIES Canadian Trailer

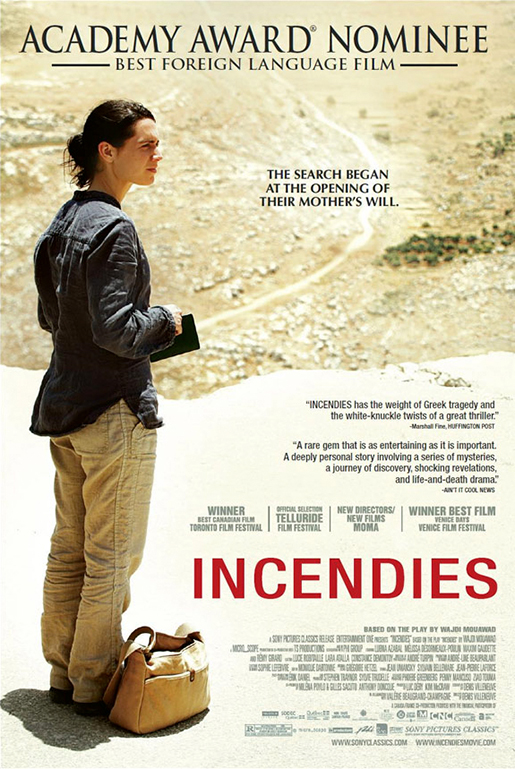

INCENDIES US Poster

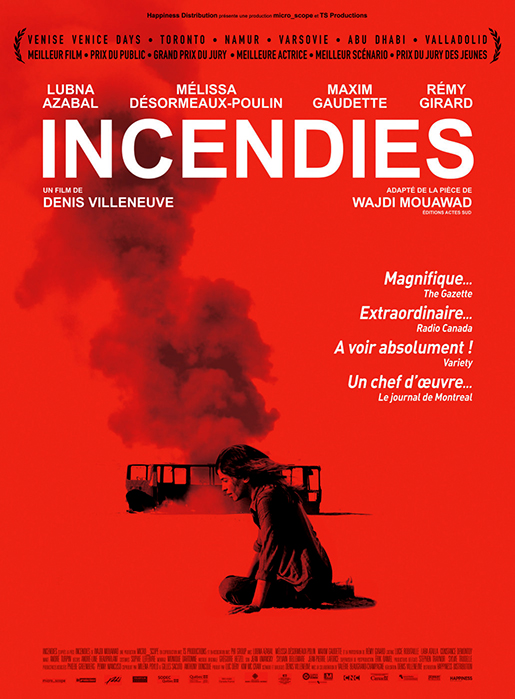

INCENDIES Canadian (Red and White) Poster

I picked up a large copy of this poster in a free bin at the Park Theatre. It was torn at the bottom, but I think it adds to it.

UPDATE: February 27, 2011

Tonight at the Oscars, Incendies lost the Best Foreign Film award to Denmark’s In A Better World by Susanne Bier, director of Brothers (2004) and After the Wedding (2006). I have to reserve judgment until I see the film when it opens in March. However, if Incendies had to lose, I would have gotten a big kick had Greece’s audacious black tragic-comedy Dogtooth taken the prize.

UPDATE: March 10, 2011

The Genie Awards has called Incendies the Best Motion Picture of 2010. Denis Villeneuve picked up two awards for Best Direction and Screenplay. Lubna Azabal also deservedly won the Best Actress award for her astonishing portrayal of Nawal Marwan.

UPDATE: March 30, 2011

The first three chilling minutes of Incendies.

© 2008 – 2024, CINELATION | Movie Reviews by Chris Beaubien. All rights reserved.