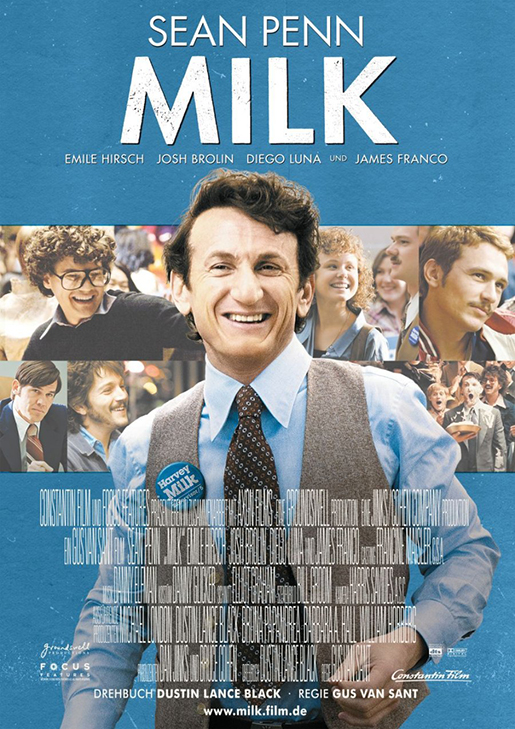

Movie Review: MILK (2008)

![]()

Vote for Harvey Milk (1930 – 1978)

The passing of Proposition 8 across the United States two weeks ago adds more urgency to the new Gus Van Sant film Milk. It is a red alarm crying out against the continued and criminal persecution of homosexuals. Denying the civil rights of an individual to legally marry a person of their choice is cruel. For decades, sanctimonious hypocrites have relentlessly imposed their prejudice on homosexuals, forcing them to live in the margins of society. Homophobia has always puzzled and irritated me. When I was seven, before I was aware of gays and lesbians, I casually wondered if there were men who loved men and women who loved women. Later I found out my musing was correct – and like looking up at the sky to see birds were flying up there — I was cheered by the prospect. As a level-headed straight man, I support and empathize with good people like Harvey Milk.

Gus Van Sant has made the most compelling biopic since Bennett Miller’s Capote (2005) – a close second is David Fincher’s Zodiac (2007) about Robert Graysmith’s obsessive investigation for an infamous serial killer. All of these films avoid the wearisome narrative trap that checks off the birth, the childhood a la Taylor Hackford’s Ray (2004). Close attention is paid to set us in this very specific time and place from 1970 to 1978 in Castro, San Francisco. For anyone unfamiliar with Harvey Milk (Sean Penn), the film reveals in its first few minutes that the man was assassinated in the late 1970s along with Mayor George Moscone (Victor Garber). The film seamlessly combines documented footage from the excellent Rob Epstein documentary The Times of Harvey Milk (1984) into the staged fiction with success much like Mary Harron’s The Notorious Bettie Page (2006). Even Milk, the first openly gay man elected in government as a city supervisor, realized his imminent death was soon approaching. Late one night, he recites his memoirs on a tape recorder in his kitchen. We come back to Milk and his mike throughout his story; his words illuminate events after the fact like an angel reminiscing until he has to stop.

Forty-year-old Harvey Milk, a closeted gay man working like a cog for a corporation, was dissatisfied with his life. Upon a chance encounter on the steps of a New York subway, Milk coyly picks up a thirtyish sweet-faced hippie named Scott Smith (James Franco, very good here). The two men light up as they fall comfortably in love. It is a great pleasure to watch their warm and attentive romance – these people are happy together. Eventually they immigrate to San Francisco where they still face open hostility and are not welcomed in stores. As a Goldwater Republican, Milk becomes vocal over homosexuals’ civil rights and initially reasons that it is against the free market for businesses to refuse service to a legal consumer just because they’re gay. For years, the police have rounded up, beaten, and sometimes murdered homosexuals for being seen in bars or simply strolling on sidewalks. There is an amazing visual of a blood-spotted metal whistle (gay people wore them as a precaution at night in case they were ambushed by thugs) lying on the road and its reflection shows us a dead man on a gurney being rolled away while Milk argues to no avail with a discontented cop at the site. Strange how something so incidental illustrates a bigger picture.

Forty-year-old Harvey Milk, a closeted gay man working like a cog for a corporation, was dissatisfied with his life. Upon a chance encounter on the steps of a New York subway, Milk coyly picks up a thirtyish sweet-faced hippie named Scott Smith (James Franco, very good here). The two men light up as they fall comfortably in love. It is a great pleasure to watch their warm and attentive romance – these people are happy together. Eventually they immigrate to San Francisco where they still face open hostility and are not welcomed in stores. As a Goldwater Republican, Milk becomes vocal over homosexuals’ civil rights and initially reasons that it is against the free market for businesses to refuse service to a legal consumer just because they’re gay. For years, the police have rounded up, beaten, and sometimes murdered homosexuals for being seen in bars or simply strolling on sidewalks. There is an amazing visual of a blood-spotted metal whistle (gay people wore them as a precaution at night in case they were ambushed by thugs) lying on the road and its reflection shows us a dead man on a gurney being rolled away while Milk argues to no avail with a discontented cop at the site. Strange how something so incidental illustrates a bigger picture.

Milk is determined to take back the Castro neighborhood as a safe haven and work up to the nation state by state. Inside Milk’s modest camera store is substituted for his electorate office peopled with idealistic gays like Cleve Jones (Emile Hirsch), Anne Kronenberg (Allison Pill) and Dick Pabich (Joseph Cross) acting as Milk’s campaign staff. Scott plays the feminine role in their relationship; he vacates Harvey’s campaign staff from their apartment so he can serve his man dinner. Upon both my viewings in a movie theatre, Milk’s response after trying the spaghetti has always gotten the biggest laugh.

After Milk gets his first death threat while running for office, he glibly tells Scott that his death could win him “the sympathy vote.” One of his most vocal enemies came in the form of Anita Bryant, a wholesome-looking singer/celebrity who plugged Florida orange juice and spread hatred against the gay movement by masking it as Christian values. She even states that the Jews and Muslims are going to hell, but that doesn’t get much screen time. After years of campaigning, defeats, sacrificing, rallies and networking, Milk became the first openly gay politician to be elected into government: “Now that’s something to fear — a gay man with power!”

While Bryant’s hatemongering escalates, a sleazy conservative state legislator John Briggs (Denis O’Hare) joins her by sponsoring California Prop 6, a bill that would ban gays, lesbians and gay rights supporters from working in public schools. To discourage the threat of homosexuality by making it more socially unacceptable, Briggs argues weakly that it is to protect children from molestation. Milk (along with political activist Sally Gearhart, who is absent from the film) pops Briggs’s argument with statistics that heterosexual males are usually found out to be child molesters: “So you’re saying the state’s population is equal to the percentage of child molestation.” Then Briggs buries his case by admitting that child molestation cannot be prevented, “…so let’s cut our odds down! Let’s take out the homosexual group (5% of the state’s population) and keep the heterosexual group (95%)!” It is no surprise when they debate in Orange County, Brigg’s turf, that the audience members boo Milk’s brilliant counterattacks that turn Briggs into a sore loser. For audiences today, the battle over Prop 8 today will mirror the one over Prop 6 that took place thirty years ago.

The Mini-Musical “Prop 8”

The Greatest Unifier Is Greed

Milk sees how a segregated group of people suffer the most when hiding from public eye. One of these is of Jack Lira (Diego Luna), a Mexican American involved with Milk for a time, is so neurotically insecure in their relationship partly because his options both geographically and politically have been so limited. Lira hinges on desperation and does not have room socially to tend his own emotional well-being. Milk, alas, tries to convince Lira that he is loved.

Another strong demonstration of how claustrophobic the times were: When Milk gets a phone call one night from a sobbing young man from Minnesota considering suicide. He tells Milk that his parents want to admit him to a hospital tomorrow to “get (him) fixed.” Milk tries to convince the youth that there is nothing wrong with him, God does not hate him, and that he should get away to New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco, anywhere. The next establishing shot of the young man (it’s not what you’re thinking) is heartbreaking.

There is even consideration for how willing Milk himself was to come out of the closet at his age while he was encouraging younger people to do so and risk standing with their family and friends. Again, the way to fight prejudice is to familiarize homosexuality with people they know. Standing out and being recognized is the saving grace that can change ignorant prejudice to open-mindedness — or at least tolerance. “Never use the elevator!” Harvey tells Cleve on the steps of City Hall, “You make such a grand entrance by taking these stairs!”

The most fascinating case study is of Dan White (Josh Brolin), a city supervisor who gambles political standing by attempting an alliance with Milk, which is tempered by his conservative upbringing and beliefs. Milk and his staff quietly speculate that White, a husband and father, might be a closeted homosexual. White argues with Milk about the sanctity of marriage, yet gladly invites Milk to his son’s christening – later his wife questions them about how “appropriate” it is to discuss homosexuality in a church. Tense scenes of Milk versus White are usually composed with an abundance of space surrounding the two overhead within the frame. At one point over professional jealousy, White belittles Milk’s crusade as an issue. On two different levels – politically and personally – Milk fiercely tries to overturn White’s accusation as being a matter of life and death. Josh Brolin, having an excellent year with this and his riveting lead performance in Oliver Stone’s W., does a commendable job playing White as conflicted, oblivious and unsettled by his own nature. There are layers revealed of White that Brolin rightfully downplays because his character lacks introspection and the willingness to look at himself more closely.

The most fascinating case study is of Dan White (Josh Brolin), a city supervisor who gambles political standing by attempting an alliance with Milk, which is tempered by his conservative upbringing and beliefs. Milk and his staff quietly speculate that White, a husband and father, might be a closeted homosexual. White argues with Milk about the sanctity of marriage, yet gladly invites Milk to his son’s christening – later his wife questions them about how “appropriate” it is to discuss homosexuality in a church. Tense scenes of Milk versus White are usually composed with an abundance of space surrounding the two overhead within the frame. At one point over professional jealousy, White belittles Milk’s crusade as an issue. On two different levels – politically and personally – Milk fiercely tries to overturn White’s accusation as being a matter of life and death. Josh Brolin, having an excellent year with this and his riveting lead performance in Oliver Stone’s W., does a commendable job playing White as conflicted, oblivious and unsettled by his own nature. There are layers revealed of White that Brolin rightfully downplays because his character lacks introspection and the willingness to look at himself more closely.

Curious how after the main title sequence, its credits are in small, meek and sans serif font, showing documented footage of gay men in bars being harassed by photographers and policemen. One patron, hiding his face with his hand, eventually throws his drink at camera’s lens. Another shot shows policemen forcing homosexuals into the back of a paddy wagon until there is no room to move. Just as Milk is about remember the past eight years, a title card blows up the screen reading “milk” in heavy white font (either Calvert or Memphis) on black. I think the second showing of the film’s title was done to change the overall tone between Milk then and Milk NOW, larger than life.

At one point, Van Sant blows up many of Milk’s campaign posters across the screen against vibrant colour with typeset so authentic you could smell the ink off the silk-screen press. Much later, a shocking moment is shown a little more warped by a framed curved mirror imaging violence from a distance. A recent collaborator of Van Sant’s is director of photography Harris Savides (Zodiac – David Fincher, 2007 – also shot in San Francisco) who soaks the images with an immediate grainy, brightness. Van Sant takes liberties with inspired camera angles when recreating scenes in the Rob Epstein documentary The Times of Harvey Milk (1984 – it was narrated by Harvey Fierstein, a gay, gravelly-voiced actor famous for The Torch Song Trilogy, 1988) such as when Harvey triumphantly rides on top of a convertible in a parade and where Milk and Briggs debate in a school gymnasium. Even small touches like the zoom-in on Dan White’s televised political running-bid make the film feel a little younger in spirit. Milk’s later recollections over the phone to Scott of an opera called Tosca may remind viewers of the best scene in Jonathan Demme’s Philadelphia (1993) where the Tom Hanks character Andrew Beckett explains his enthusiasm for his favorite Maria Callas operetta Madeleine.

In the Danny Elfman score, there are occasionally off-kilter guitar strings that provide tension against the soulful saxophones and violins (Yes, I own the soundtrack). On the track Gay Rights Now, there is a soaring, almost angry melody that makes me sit up a little straighter. When Anita Bryant is introduced, Elfman’s score sounds very much like Suzie’s Theme from To Die For (1995 – my personal favorite of all the Gus Van Sant films and one of 1990’s very best) with its loony cheer and chilly choir singers. Van Sant uses damning footage of Anita Bryant to play herself, a tactic used recently by filmmaker George Clooney with U.S. Senator Joe McCarthy in Good Night, and Good Luck (2005).

For Sean Penn, one of the most accomplished American actors working today, this is one of his most accomplished performances. Penn hasn’t been this on target since he played real-life thwarted terrorist Samuel J. Bicke, an insecure, emotionally-turbulent, divorced American salesman who attempted to hijack an airplane to crash into the White House, in Niels Mueller’s The Assassination of Richard Nixon (2004). Famous for his darker, angrier roles (Tim Robbins’ stellar Dead Man Walking, 1995), this attentive and happier one is a revelation that harkens back to his sensitivity from Woody Allen’s Sweet and Lowdown (1999). In Bicke, Penn portrayed excruciating agony within a soft, breaking shell. Here in Milk, Penn thrives with generosity, rage and joy as a rebellious spirit with the courage to uphold a watershed against bigotry. Those two roles are polar opposites, yet Penn excels at fearlessly embodying them with honesty. Like Philip Seymore Hoffman’s versatile turn as Truman Capote, Penn captures the essence of Harvey Milk without relying on an imitation of an earlier performance. Showcasing the wise casting and thoughtful performances before the end credits, archival footage presents first the actors and then their real life counterparts from the The Times of Harvey Milk, the people surrounding Milk, detailing what happened to them. With perhaps a little more stress on the voice than needed, Penn’s Milk comes scarily close to the real thing.

For Sean Penn, one of the most accomplished American actors working today, this is one of his most accomplished performances. Penn hasn’t been this on target since he played real-life thwarted terrorist Samuel J. Bicke, an insecure, emotionally-turbulent, divorced American salesman who attempted to hijack an airplane to crash into the White House, in Niels Mueller’s The Assassination of Richard Nixon (2004). Famous for his darker, angrier roles (Tim Robbins’ stellar Dead Man Walking, 1995), this attentive and happier one is a revelation that harkens back to his sensitivity from Woody Allen’s Sweet and Lowdown (1999). In Bicke, Penn portrayed excruciating agony within a soft, breaking shell. Here in Milk, Penn thrives with generosity, rage and joy as a rebellious spirit with the courage to uphold a watershed against bigotry. Those two roles are polar opposites, yet Penn excels at fearlessly embodying them with honesty. Like Philip Seymore Hoffman’s versatile turn as Truman Capote, Penn captures the essence of Harvey Milk without relying on an imitation of an earlier performance. Showcasing the wise casting and thoughtful performances before the end credits, archival footage presents first the actors and then their real life counterparts from the The Times of Harvey Milk, the people surrounding Milk, detailing what happened to them. With perhaps a little more stress on the voice than needed, Penn’s Milk comes scarily close to the real thing.

Funny story: After Penn kissed Franco for the first time, he called his first wife Madonna to tell her the kiss reminded him of her. What does that mean, Doctor Freud? I guess we’ll never know.

In the Epstein documentary, White was actually more intolerant of gay rights and gave speeches in that vein inside Orange County churches that the Van Sant film doesn’t show – the director just wants to keep the conflict between Milk and White at a personal level. Much of the documentary after Milk’s assassination focuses on White’s trial which was presided by a jury of White’s actual (read: white, heterosexual) peers because the court felt that inviting a homosexual into the jury box would be biased. Wait till you hear about the Twinkie Defense™! White’s recorded testimony over the day of the shooting is pathetic: “(Milk) just kind of smirked at me. ‘Too bad.’ I just got all flushed and hot and I shot him.” The jury really did weep for White and pardoned him with five years in prison for murdering two civil servants of the state. Sometimes, good things happen to bad people.

Eventually it struck me how much I missed Harvey Milk in the documentary. Van Sant keeps Milk on screen in his film for as long as he can. The limited time he uses afterward is to mourn. For a film that sounds grim and serious, Van Sant counters Milk with so much enthusiasm and comedy that his ultimate fate is even more tragic. One of the most astonishing pieces of footage is reserved near the end of the film to show how many people Milk had spoken for. You could almost hear Milk, like a phantom voice, calling aloud “My name is Harvey Milk and I am here to recruit you!” With Milk gone, he would have been seventy-eight years old today, those same people were more free to continue the revolution of making their own voices heard. They became an army of hope.

Keith Olbermann’s “Special Comment” from MSNBC Countdown

MILK (2008) Trailer

<

MILK (2008) TV Spot

THE TIMES OF HARVEY MILK (1984) Trailer

3 Reasons: THE TIMES OF HARVEY MILK (1984)

© 2008 – 2024, CINELATION | Movie Reviews by Chris Beaubien. All rights reserved.