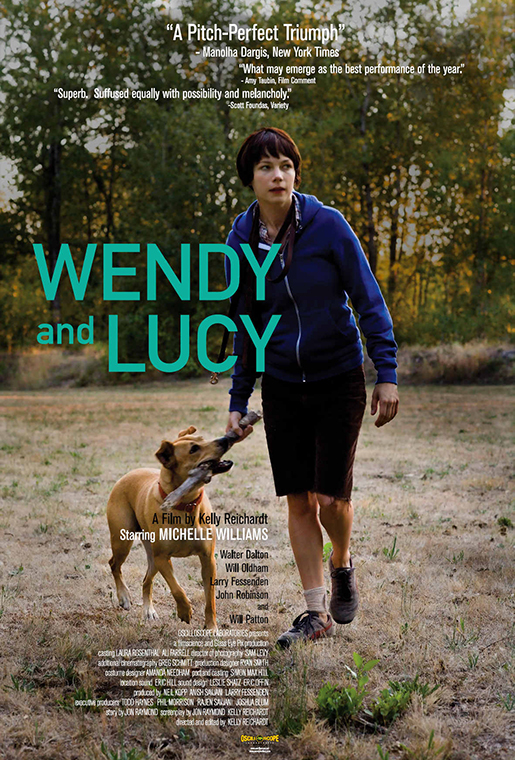

Movie Review: WENDY AND LUCY (2008)

![]()

Poor in Show

Quietly, slowly and efficiently, writer and director Kelly Reichardt observes Wendy (Michelle Williams), a young runaway disenchanted with her life back home and who is dangerously close to becoming a drifter. Invisible to those around her, she is accompanied by Lucy, her golden retriever. She also wants to find work in Alaska. Wise choice: the fish canneries do pay well. The two sleep in her car. Her budget is really tight. Now her car won’t start. Over the next few days, she is stranded in a nearly desolate Portland, Oregon town where she curtly explains to strangers: “I’m just passing through.” With many miles left to go and too far away to go back, Wendy is determined to stick to her plan.

In a wonderful shot early one morning, Wendy lugs out a nearly empty extra-large bag of dog food out of her car to fill Lucy’s bowl near a suburban curb. Under an overcast sky, the shot stays with Wendy and then she leaves the frame. From a low-angle, we observe a line of modestly kept homes at a distance. There is someone sitting in one of the porches looking back at us. Who is this person? Is this important to the plot? Where’s the movie star? This is a waste of money! The studio notes would have been endless had this not been an independent production outside the studio system. Wendy does come back into the frame. The means of losing her momentarily demonstrates just how easily she could slip right through the cracks and never be seen again.

Michelle Williams is a chameleon — she shreds all semblance of her earlier, more glamourous roles. All that’s left is Wendy, fresh-scrubbed, a haircut from home and eternally clad in plaid shirts and faded jeans. Is this really Jen from Dawson’s Creek? Now, Wendy is distraught and apologizes to her dog for the few crumbs she able to offer. Then she goes to the supermarket a few blocks down. When currency-conscious Wendy decides to steal a few items from the store, I was really touched by what she left behind in the store.

Now, I would like to single out the score by Will Oldman, who also plays Icky, the free spirit by the bonfire, as well as the aged hippie Kurt in Reichardt’s previous Old Joy (2006). The most minimalist music here is also the most haunting. It consists of Wendy humming to herself a few bars of prolonged, wistful notes. What most people fail to recognize are a few omnipresent tones from a flute that play between the empty breaks. This score is like the zither music played by Anton Karas in Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949). It’s simple, impressionable and the most economical due to Michelle William’s unforced vocal chords. Every time I hear it, my eyes sting a little. I know how lonely it can get when a few carefully placed hums can make one appreciate the poignancy of it all.

The cinematography by Sam Levy uses shadows and open space to present the chilly beclouded surroundings. Reichart joins forces with Mike Burchett in the editing department; they maintain the essence of their shots without imposing unnecessary cuts to impose their self-importance.

The most corrupt of the people Wendy encounters is Andy (John Robinson), a beefy teenager employed as a stocking clerk who catches her shoplifting. He goes too far manhandling her back into the supermarket, making her cry out, “You’re hurting my arm!”

His self-entitlement is sickening when he exposes Wendy as a thief to his manager behind the desk. Andy wears a cross around his neck that is so large and gold that it stops being a sign of his faith and only functions as bling. Continuing his tirade of black-and-white naiveté, a student of extremism, he just about bullies his boss into siccing the cops on Wendy: “We have a no tolerance policy on shoplifters!” Wendy, however, is concerned about Lucy tied to the bike rack outside. Here we get a crucial piece of dialogue by the sanctimonious Andy: “If a person can’t afford dog food, they shouldn’t have a dog.” So poor people don’t deserve the love of one of God’s noblest, least judgmental of creatures? That’s Andy the Christian, ladies and gentlemen. Wendy and Andy do meet again later in a scene that is so probable that’s it’s a wonder that it was written. The way Andy goes back home is priceless. It’s perfect.

Wendy is like the American descendant of that doomed, aimless drifter Mona Bergeron (Sandrine Bonnaire) in Agnès Varda’s Vagabond (1985). The beginning of Vagabond established that Mona (is that even her real name?) died anonymously of hypothermia in a ditch while the rest of the film recoils from reflections and recollections of strangers she met on her travels. Many of the people Wendy came into contact with would surely hold limited impressions of her like we would of Wendy and everyone else we come into contact with.

The act of forging relationships through happenstance, no matter how intimate they are, is crippled by how we can never truly know another person other than ourselves. Both of the 1972 Tarkovsky and the 2002 Soderbergh versions (the Soderbergh one even more so) makes this case successfully: The hallucination of the alive Rheya, the dead wife of Chris Kelvin (George Clooney), is suicidal because that’s what he thought she was. What Wendy will have to endure after the last few slides of rolling celluloid, we are not permitted to see.

Without forced contrivance, all Reichardt wants from us is to share the concern and care she has for her title character. We pick up little information along the way such as a phone call back home that tells us just enough. I suspect that some audience members won’t be sympathetic to Wendy; a similar case study determining an individual’s degree of empathy measured by my patented Kathy Nicolo Litmus Test. The title character played by Jennifer Connelly in House of Sand and Fog (2005) was a struggling, insecure Alcoholics Anonymous member who met devastating consequences for making trivial mistakes. Some people I have come across just loathe Kathy Nicolo whereas I am levelheaded in my heart: for the grace of God, go I. Yes, Wendy should not have shoplifted dog food that one morning but she did not deserve to lose her one companion. Yes, Kathy Nicolo should have opened her mail but she did not deserve to lose her home.

Circumstances get so bad that we witness Wendy spend her first night sleeping in the woods. What happens later that night is frightening. Thank goodness Wendy meets a couple of good souls such as the security guard (well played by Wally Dalton) who watches over a store nobody goes to because just about everyone else is unemployed. Watch how Dalton regards Wendy as she talks on the cell phone he lets her borrow: He studiously measures the amount of time he can look at Wendy as an acquaintance while avoiding the act of staring. The amount of money he gives her says much more about his poverty than his generosity.

The title Wendy and Lucy is a perfect marriage between the two protagonists. Together, all is not lost. They love each other unconditionally. Alone, that’s when it gets scary. Wendy arguably needs Lucy more because her dog is the last remnant of a life that was once grounded. Lucy is the only bright speck Wendy wants to keep in a dismal existence she wants so much to overcome. Wendy and Lucy is the story of a woman and her dog like Ken Loach’s Kes (1969) is the story of a boy and his hawk.

It is worth noting that Reichardt employed her own dog, also named Lucy, in her film. This is Lucy’s second performance on film after playing a supporting character in Reichardt’s contemplative Old Joy about two thirtyish men, friends from college and now separated by class, who spend one weekend together finding a secluded hot springs. They listen to NPR while driving, talking serenely of the past and hesitantly about their futures. When the hot springs is finally discovered, it later creates enough space for the viewer to vicariously feel at peace for a little while. On the DVD commentary track, Reichardt confessed that she looks for stories that has a dog in it.

The purpose of independent film has been eroded for over a decade of new filmmakers making quirky, action blockbusters Hollywood regurgitates within a low-budget. An army of talent auditioning for the attention of producers promising the big bucks for making low-brow, escapist fare. It is rare to find members of the next generation of Cassavates; those who seek to make a film from out of their hearts and revile the compromises of greed and box office approval. Kelly Reichardt is like the kid who would rather make sand castles outside in drizzly weather while the others kids stay inside to text message each other. She rebelliously makes deliberately small-scale films that economize on staying power through simplicity, humility and nerve. The character Wendy is just as stubborn. She is frustrated by every single bad break that would convince believers that a wrathful God is dedicated to her destruction.

At the end of the film, we see just how great a heart Wendy does have when pressed so hard it hurts. We are left with one important question: Will she come back? I can’t know if she will, but I hope so.

WENDY AND LUCY (2008) Trailer

OLD JOY (2006) Trailer

Now that’s what I call Film Grain.

© 2008 – 2024, CINELATION | Movie Reviews by Chris Beaubien. All rights reserved.