Movie Review: SYNECDOCHE, NEW YORK (2008)

The Life Stages of Caden Cotard

Oh God, I feel alone. I feel so utterly alone having connected and clicked with a film that many people will reject. This being the directorial debut of the incomparable screenwriter Charlie Kaufmann: Sï-nêk’dõ-kë, Nyöo Yáwrk. For me, Synecdoche, New York is a tough sell — an unconventional film that I treasure where recommendation demands caution. It’s where I stand with Béla Tarr’s Werckmeister Harmonies (2000), Lars Von Trier’s Breaking the Waves (1996), Bill Forsyth’s Housekeeping (1987) and Robert Altman’s Three Women (1977). These films fly in the face of all the formulaic and commercial creeds of how a movie should work and gives pause for how many ways it could work best. A first impression might grimace, conclude “it’s weird” and close the investigation — that’s their right; however, Synecdoche, New York deserves better and an appreciative audience. The film works, not despite, but because of its extraordinary structure and function being mysterious, opaque, labyrinthine, yet emotional, accessible, and fully-formed.

What I love most about Charlie Kaufman’s exercises in the celluloid medium is how they exceed expectations throughout his most unorthodox and dizzying narratives. Throughout, there is apt teasing and suspense over where this story could go when driven by such a visionary. By the end, I feel as if he has exhausted every possibility from his premises with an attentive heart. Such as when the pitiable Craig Schwartz whose puppets of himself and Maxine, a distant female co-worker, kiss for the first time in Being John Malkovich (1999). Or when Joel Barish frantically races away from his evaporating memories with his ex-girlfriend Clementine at hand, trying to save her in Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (2004). Or how about when in Adaptation (2002), New Yorker writer Susan Orlean is struck by the awesome poetry of John Laroche, a toothless orchid thief, musing about the “little dance” between wasps and orchids — “How, when you spot your flower, you can’t let anything get in your way.”

In Synecdoche, New York, our hero tries to find meaning in his very existence by resurrecting an evolving metropolis in a gigantic sound-stage where a flock of birds fly off many miles down the structure. The seminal replica of Manhattan is a theatre set for an untitled play about its director and all of the people in his life. Since the play reflects life, so the play must reflect itself like a microcosm that expands, refracts, grows and deepens. It is a comic-tragic, universal illustration of a life that tries to manage its surrounding citizens in roles (wife, daughter, mistress, 2nd wife, etc.) the participant tries to contain. Of course, everyone else is the lead in their own story, so management of the play of one’s life becomes discombobulated.

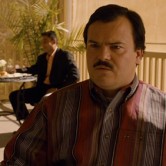

Enter the world of theatre director Caden Cotard played with great nerve and without vanity by Philip Seymore Hoffman. At age forty, he is burdened with anxiety, bad health, failed relationships, and occasionally distracted by lofty goals that feed his great ego which barely hides his low self-esteem. Like an addict, he mercilessly prods, analyzes and compresses his failures; denying himself a much wanted recovery by purging himself deeper into a sea of emotional toxin. What hurts most is that he tries so hard to preserve what little he has left. While a doctor sews stitches into his forehead after a freak accident with an exploding sink faucet, Caden sheepishly remarks, “I’d rather there not be a scar.”

Ailments arrive and roost inside him at an alarming rate. Every checkup by one doctor leads to the discovery of another problem (“My pupils don’t work.”) and the recommendation of another doctor for it. Caden’s body with its cramps, bleeding gums, oozing pustules, and strange bumps consistently fails him with a vengeance. If his body were a temple, the city council would demolish it in favor of clearing the real estate for a shiny high-rise. A man this sick cannot be happy and cannot really live. But for all his flaws and succumbs to temptations, he keeps trying.

Life at home is just as damaging. Meet Adele, his wife, a moody and exacting painter who paints on canvases so small that she and her patrons require magnifying goggles to make out the beautifully rendered figures. Her proposed all-night task of packaging her work for her Berlin exhibition is a gut-buster. Catherine Keener (again opposite Hoffman in Bennett Miller’s Capote back in 2005) makes such a strong impression as Adele with her stringy hair, a tattooed breast, and a haggard complexion verging on desperation that her absence later is deeply felt. The character is richer because Keener manages to exude compassion and comfort within what a lesser actress would make one-note and abrasive. It makes sense why these two flawed and ambitious people would have tried to make a life together with their four-year-old daughter Olive (Sadie Goldstein).

Just about everyone is sick here. Adele coughs a lot, even in voice-over when a letter by hers is read. She ignores Olive’s frightened insistence that her feces is a strange colour. Caden and Adele’s flaky, stone-faced couples counselor Dr. Madeleine Gravis, played by scene-stealer Hope Davis (American Splendor, 2003 — Is Harvey Pekar around here?) — her feet are raw with angry red and white blisters irritated by her sleek, black high stilettos — even this leggy blonde is flawed. Deliberate attention is paid to the deterioration of the human body weathered by age and disease.

Vulnerably and mortality is emphasized with the perplexing passage of time; months, even years pass within minutes. Going from the bathroom on September down the stairs to the kitchen; suddenly it’s October. Where did the time go? What happened with my life? Has it really been six months? Six years! Conversations with the Cotard family feel rushed, overlapping dialogue, even precious moments with Olive feel short-lived instead of cherished. Fasten your safety belt — this film will give you whiplash.

Madeleine commits the obvious scam that all best-selling shrinks must, bringing to mind Richard Dreyfuss’ Dr. Leo Marvin in What About Bob? (1991). It doesn’t help that Adele dismisses Caden as an artist since he works with previously adapted material, while overlooking his radical realization of the play Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman. In an instant, Caden has lost his family abroad, romances sparks from the advances of Hazel (Samantha Morton, Morvern Callar (2002)), a 30-something buxom box-office girl to his young leading actress Claire (Michelle Williams, Wendy and Lucy (2008)), and Adele’s manipulative friend Maria (Jennifer Jason Leigh, Last Exit To Brooklyn (1990)) has sensationally corrupted Olive, and Caden wins the MacArthur Genius Grant along with surmountable freedom, financial security and infinite time pursue his most ambitious work of art! Such a grant would be evidence enough to place this film in the fantasy genre.

Then Caden’s next project gets personal.

Synecdoche, New York knows what it is to be so painfully conscious, so agonizingly aware of your circumstances that you feel belittled and judged; objectivity just gives you a better view of your own bad performance. There is something creepy, an almost sickly undercurrent throughout the film. Kaufman resists explaining away the strange materializations (eg. the fire house) and warped timeline as the result of Caden’s mentally unstable reinterpretation of the world. What Kaufman is suggesting is even scarier and more immediate than placing his story in the safety zone of “it was all a dream”. Yes, every surreal and miraculous thing that is happening before us on the screen is reality. If our perception is illusory and concrete, then it is possible for the real world to be represented with the weight barren in a dream, but nightmarish in its network of logic.

Yes, Caden can be self-absorbed (Claire is the one who figures out Hazel’s situation for him) and pretentious. Just look at Hazel’s expression as she awkward sips her drink while Caden talks about his play where “we are all in the same primordial bloodstream” (I’m paraphrasing here, I’ve only seen this movie once*). Everywhere he goes, he sees himself in advertisements, and as a character in a deranged cartoon Olive is watching. From a first-person account, doesn’t everything seem to be informing us — (read: ME!) — only more directly? Caden does not always do the right thing, but he is aware of his failures and genuinely regrets his mistakes.

A flawed protagonist is required as a launching pad for those who must identify with, but not idolize the subject. This is from someone who made self-deprecation look like fun in Adaptation: “Charlie Kaufman! Fat! Bald! Repulsive! Old! Sits at a Hollywood restaurant with Valerie Thomas!” Caden finds out later that Adele “wants joyous and healthy people (in her life)” in a way that is impersonal and devastating. Only a shallow, empty vessel trying to pass as a human being could dismiss Caden’s feelings — I’m looking at you, Ben Lyons! Appearing on the gutted remains of At The Movies, Lyons smiles like a greasy used car salesman when he calls Caden “The most pathetic individual to ever exist!” Has Ben Lyons ever left his bubble?

During a lunch outside with Hazel, one of the few times Caden is serene, she feeds him lines to woo her. He enjoys taking her dictation; playing his character instead of being himself. This scene foreshadows near the end of the film where Caden takes direction by the sound of a woman’s voice. Here, too, he is also serene. Kaufman again delivers a variety of role plays, bizarre transformations and comic scenarios including bravado turns by Tom Noonan (Snow Angels, 2008) as a sad-eyed stalker who is hired to play his stalker and Dianne Weist (Hannah and Her Sisters, 1986) as an actress who plays the only character Caden has never met (translation: a fictitious person) and vice versa. There is a brilliant inside joke by casting Emily Watson (Hilary and Jackie, 1998), as arresting as ever, to play Tammy — the stage version of Morton’s Hazel. One time Samantha Morton auditioned for a role and the director complimented her performance in… Hilary and Jackie. Awkward.

Double entendres sparkle throughout the crisscrossing storylines. Caden is asked at one point by Madeleine “Why did you kill yourself?” Caden asks her to repeat the question and she asks “Why would you kill yourself?” Two versions of her question refer to two instances with technically different characters in a real place and the same place set in Caden’s warehouse. This scenario is like a decoder device that can be applied to a variety of loosely connected scenes that reveal greater understanding to the characters’ pathos. Caden’s relationship with Sammy, the faux Caden, emphasizes how competing with others for the heart of another is as bad as competing with oneself. Throughout the film, Caden’s worst enemy is really himself, whereas the older he gets, the lonelier and less significant he feels.

Women surround and sometimes dominate Caden who, in a very tender scene, admits to Tammy in private that he secretly wanted to be a woman: “Maybe I’d have been good at it.” We hear a little Kaufman himself inserting sparse commentary through his characters, particularly when Claire talks about the thrill of “working with so many strong, female actresses” in a play. Caden attempts to form a bond with the flirtatious Hazel to rebound from his failed marriage (“Can you help me forget my troubles?”). In the middle of sex, Caden breaks down and tries to let Hazel down gently and then the camera focuses solely on Hazel — from Caden’s pain to hers. In fact, Hazel may be the only character who has screen time where Caden is absent.

Observe how unsentimental Kaufman is about his characters without politically correct conceits of gender; while Caden is suffering from PAS (Parental Alienation Syndrome), he psychically wrestles Marie down to the ground after being refused to see his daughter. From a sweet kid to adulthood, the case of Olive demonstrates how truthfully harsh circumstances can get for people outside the bubbled, idealistic depiction of children. Two later encounters between a much older Caden and his adult daughter are searingly painful to watch.

Coal-black social satire peels Caden’s materialistic and art-minded facade apart. In a toy store, having gotten indispensable information from Olive’s evolving diary that her favourite colour is pink, Caden purchases a large pink box with an illustration of a human nose that is titled “nose”. In the real world (re: every other movie that is not Synecdoche, New York), Caden is buying his daughter a Barbie House™. Kaufman consistently strips the layers of recognition and conventionality to expose the absurdness of everyday truisms. It is worth noting how Hazel’s answering machine never changes, which encapsulates her young self despite how the passing years have aged her. One particular phone call Caden makes to Hazel is awfully poignant.

The same twisted and delicious logic of Kaufman is on display here like the way in Adaptation, a screenwriter’s life is threatened at gunpoint by the very characters he rewrote and corrupted to make his script more commercial. For almost the past decade, Charlie Kaufmann’s scripts have turned into some of my most treasured experiences in a movie theatre. I was with Being John Malkovich every step of the way: “What happens to a man who goes down his own portal?” “We’ll see!” That directorial debut of Spike Jonze — who also played the fourth leg of a table called Three Kings that year — was a near-perfect comic-tragedy.

BEING JOHN MALKOVICH (1999) Trailer

Ministry of Information Scene from BRAZIL (1985)

The music used in the Being John Malkovich (and the WALL-E) trailer(s) is from the 1984 Terry Gilliam film Brazil; the track entitled The Office is by Michael Kamen. Come to think of it, Kaufman’s direction is rather Gilliamish AND Tatiesque (eg. Playtime, 1967). Synecdoche, New York is compacted with strange objects and idiosyncratic details — that pink Christmas present of Olive’s was not an accident — it’s memorable. The set design alone of the city spectacle with the indomitable blimp flying overhead inside the warehouse is a Terry Gilliam wet dream.

The score for Synecdoche, New York by composer Jon Brion is high-strung and whimsical with occasional alien notes. There are some playful musical cues of angst near the beginning that pay homage to Brion’s edgy track Hands and Feet (instruments included xylophone, hammers and duct tape) from P.T. Anderson’s Punch Drunk Love (2002). Here We Go, a musical number by Brion for Punch Drunk Love is in the same vein as the sleepy piano ballad Little Person sung by jazz vocalist Deanna Storey. It was also written by Mr. Kaufman. What a smoky and poignant song.

LITTLE PERSON sung by Deanna Storey

From Little Person:

Somewhere, maybe someday,

Maybe somewhere far away,

I’ll meet a second little person,

And we’ll go out and play.

There are visual clues throughout Synecdoche, New York, one of the most crucial shows us a digital read-out of 7:44 in the beginning of the film and a brick wall with spray painted clock-hands pointing to 7:45. Life is so fleeting that it could very well pass within a minute. We can’t trust our eyes, but feelings are another matter. Again, the best way to exercise this film is to take everything at face value. Synecdoche, New York shows us that the unexamined life is not worth living, but that a life worth living means enduring a great deal of pain. Because the grim subject matter is approached with an open and searing heart and a great sense of humor, the film is not depressing. I felt exhilaration and joy over the ambition, scope and warm intentions against the dying gray light.

Caden’s greatest sin is he has taken his life for granted. Proof is constantly before him — his decaying body and his deteriorating relationships with other people. The key line of dialogue early on is “I don’t feel well” and by the end, he won’t feel anything at all. Despite the realization of Caden’s extravagant metropolis stage, which is like a director’s Heaven, living in a world where everyone is constantly looking at (and like) each other, they are forever reflecting themselves. By leaps of artistic pursuit and/or madness, Caden as well as his actors can assume the role of someone else — the irony being that they are still their own selves and there is no escape from that. For better or for worse, death is being relieved of yourself. In a film that marks its viewers with such immediate finality, it is life-affirming how much longer it all could’ve gone on.

*After a second viewing, I confirmed that Caden actually told Hazel “We’re all in the same water. Soaking in our very menstrual blood and nocturnal emissions.”

December 24, 2008:

“Harold Pinter won the Pulitzer. No, wait — he died.”

SYNECDOCHE, NEW YORK (2008) Trailer

This is the best movie poster I’ve seen for the film. It’s cool how those cursed notes on the table resemble the windows of the city.

© 2008 – 2024, CINELATION | Movie Reviews by Chris Beaubien. All rights reserved.

Pingback: Rainbeau Creative Blog | Special Featured on “Synecdoche, New York” (2008)

Pingback: Rainbeau Creative Blog | Cinelation is on the LAMB