SOCKET (2016)

A doctor punishes a photographer for ridiculing her amateurish attempts at his profession.

DOWNLOAD THE “SOCKET” ELECTRONIC PRESS KIT

JUNE 2022 UPDATE:

During the pandemic I produced a new restoration of SOCKET (2016). This 21-minute movie now includes a tighter edit, new color correction and more visual effects. Going back to work on SOCKET for several months has been a joy and I hope you enjoy it too.

A crime of passion is one thing, but to inflict cruelty over a long period of time is patently evil. The short film Socket is a disturbing and darkly comic character study about Darlene Hicks (Robyn Bradley), a doctor working in a medical clinic who is at odds with her creative ambition. She reaches out to Errol Cloutier (David Cutcher), a professional photographer who visits the clinic as a patient, to validate her as a fellow artist. Right after he tactlessly dismisses her efforts, the hero worship turns toxic. Her commitment to exacting punishment on him stretches out for six months.

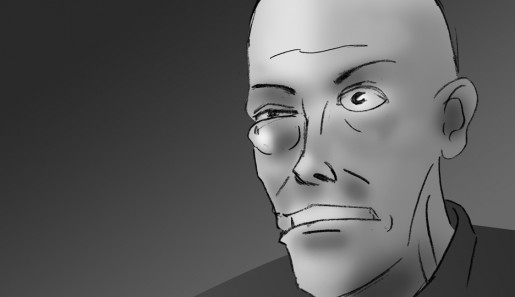

Errol suffers from a sol tumor under his eye. The bigger the tumor grows, the more his agency and sanity is jeopardized. Darlene becomes unspeakably corrupt and exploits her role as a caregiver by withholding the treatment that Errol urgently needs. Darlene’s medical profession is twisted by her desire to be a great photographer. She takes deranged joy in nurturing Errol’s disease, which she believes is a compelling subject. Thus, Darlene turns Errol into her own personal art project. Every artist needs a subject. Plus it makes her job more exciting.

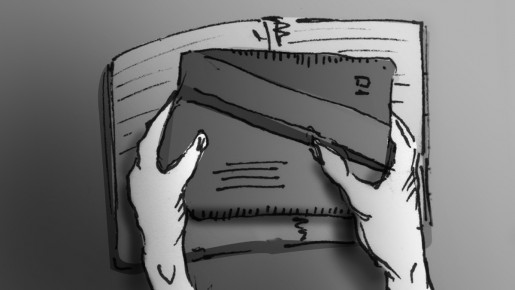

The cruelty she exacts on Errol is where she comes into her own as an artist. By creating a collage of photographs depicting the destruction of Errol’s eye, she feeds her creative impulses left dormant by her dedication and sacrifices to become a doctor. Despite the respect and power she wields with her position, her dissatisfaction is disturbing. Darlene wants to excel as both a physician and a photographer. Her ambition for more success and variety is the root of her anxiety and entitlement. To feed both sides of her brain, she descends into complete psychosis. If she is denied stature as artist, she will take over “the great artist” status in her mind by turning his elimination into art of her own.

Ultimately her course of action is self-destructive. There is little difference between her growing rage and the malignant flesh that tortures Errol. Her mission to make Errol’s life a living hell becomes her entertainment and joy. At one point the growing tumor is juxtaposed with Darlene tending to a potted plant. There is a warped maternal quality in her fascination with Errol’s cancer. She also assumes the role of film director by giving Errol placements, actions (pull the skin down from your eye), and playing gaffer with the drafting light on his face.

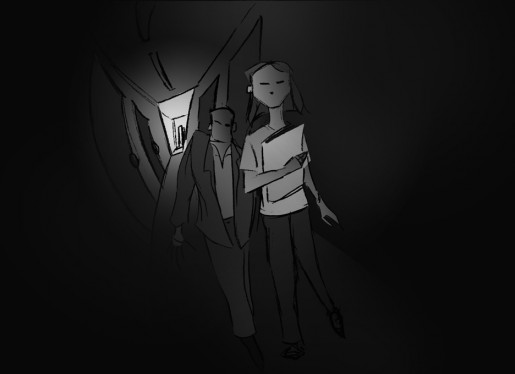

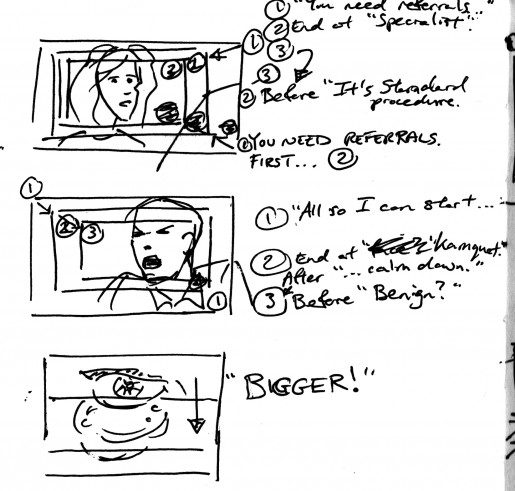

The way Darlene oversees her clinic is much like a warden tending to her sickly inmates. There is a subtle irony that Darlene’s office, where she exercises her authority with her medical degrees on display, looks more like a holding cell. Her need for control causes Darlene to treat her earnest young receptionist Mindy (Amelia Morris) like a lackey. Due to Mindy newly working in an adult field, she lacks the sophistication to realize Darlene is subtly manipulating her. Later, Darlene throws Mindy under the bus to deflect being blamed for sabotaging Errol’s crucial appointment with the surgeon. Feeling doomed and helpless, Errol takes out his pent-up rage on emotionally abusing Mindy, bringing her to tears. Darlene’s toxic power play is emphasized as she wipes her protégé’s nose with a tissue like a mother does to a child.

It is no coincidence Errol calls Mindy a “worthless child”. Both adults patronize Mindy, who is in her early twenties and eager to please in her first job. There are a number of parallels between how these three treat each other. For instance, Darlene’s admiration for Errol in the beginning is spoiled when he puts her down. This is reflected by Mindy who has sympathy for Errol’s suffering from cancer — that is until he lambasts her. Like Darlene, Mindy feels raw and bitter towards him, even calling him “a freak” when he attacks her for his medical file.

Illness is also depicted through the juxtaposition of the waiting room’s nasty head colds: Mindy blows her nose, not becomes she’s sick, but due to being upset by Errol’s venomous insults. The one time Darlene coughs is after her murderous brawl with Errol. It is ironic that Errol looks the most comfortable and healthy reading his book among the very sick at the beginning. Even the way Darlene remembers (visualizes as though she can zoom in on her past point- of-view) just how puffy Errol’s eye looks. That moment carries a sinister undercurrent that Darlene has the power to will the infection into becoming malignant.

Errol is grotesquely transformed, both mentally and physically over time as the tumor debilitates him from doing anything he enjoys. Darlene remains apathetic towards his plight as she fulfills her dream, framing his eye, yet cold towards the suffering inside. Errol’s paranoia and rage sends him into insanity. By Christmastime, his black overcoat and cane makes him look like a villainous figure of death. He is perfectly matched by Darlene whose white coat gives her the dynamic presence of a mad doctor. Is it any wonder they have a final confrontation where the emotional violence turns to real bloodletting?

The passive aggressive vindictiveness between these two escalates into an all-out war. Errol’s ultimate defeat comes at the loss of his hands during their vicious brawl in the examination room. An artist (and especially a doctor) needs both sight and dexterity. Darlene wins her own validation as an artist through the realization of her vision. A doctor’s stock-in-trade is human anatomy. Darlene seizes complete control over Errol’s body by molding him into her greatest creation – a black hole only she has the imagination and resources to conjure.

Having placed Error up on the pedestal representing the status of “great artist” she sorely wished to share with him, and failing to make the grade, Darlene must destroy him in order to take his place. Even when she tortures him as a physician, she still places him high on the examination table. By removing his faculties to criticize and discourage her – namely his eyes and consciousness – she comes into her own by using established doctor’s tools: the Popsicle sticks. To her, he is an art project, no different than a lump of clay to mold. Like a sculptor, she must get her own hands dirty.

There is a fitting irony in that Darlene retains her eyesight; she is blinded by her overall circumstances. As a paramedic wheels her away on a gurney, more fitting for a corpse heading towards a morgue or an inmate being transferred to a criminally insane asylum, she is never happier lost in her own madness, actually seeing the end result of her photography sessions, a black hole where Errol’s eye used to be. High on delusion, she finally has work she can proudly display on her wall. It is a mercy that Darlene is oblivious to the forensics expert taking pictures of Errol’s corpse in the crime scene – she’d sue for intellectual property.

Speculation is key to driving suspense. In order to engage the audience’s participation, the design of the movie is to ignite curiosity, fascination and mounting dread. Its pace consists of long shots and reflexive glances akin to a predator’s attack – very subtle and disquieting. The success of the experience depends on how many hearts bang violently in the chests of the audience.

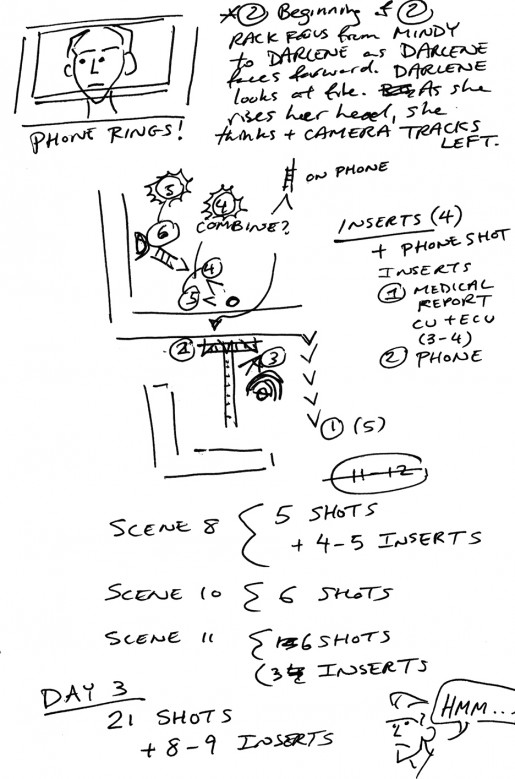

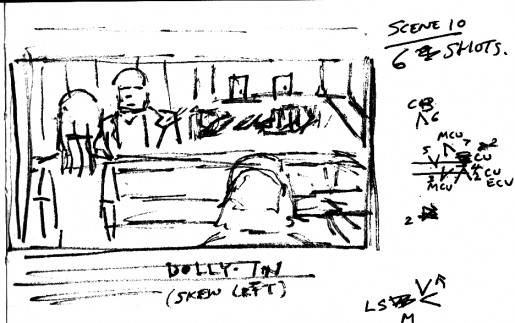

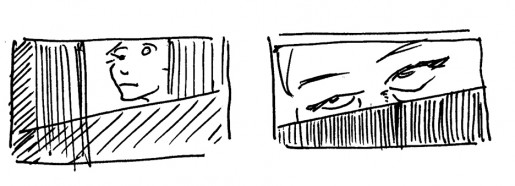

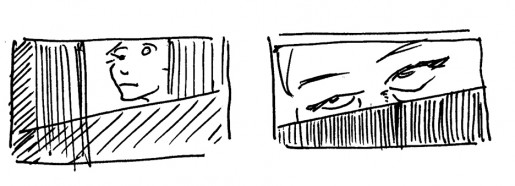

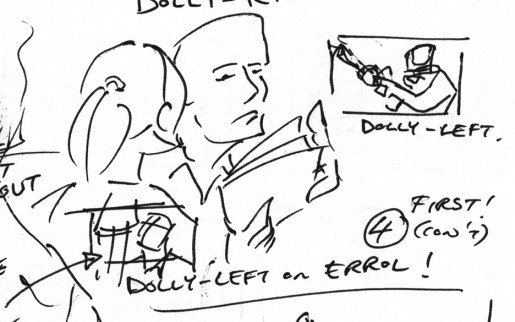

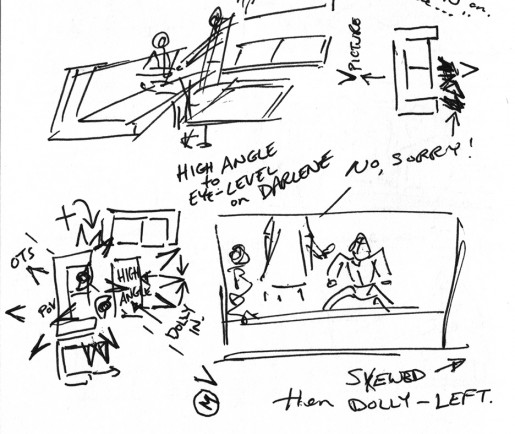

The studied and skewed cinematography reflects Darlene’s bitter worldview. The sights subtly encompasses high and low angles that gain exaggeration throughout moments of dramatic flux. The camera movements possess a sly, informed perseverance. How we see the characters and their actions in the frame is crucial for a movie about the act of seeing, creating and losing the ability of both. The impression of growing obsession is paramount.

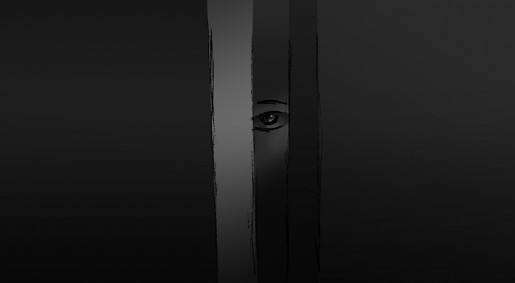

The anxious and morose tone of the story reverberates with dark shadings and shadows. The lighting emphasizes darkness. Even daylight feels sunken and sinister. True blacks and greys are solely present by filming in black-and-white. The visual scheme gives the film a transformative quality that can veer easily into noir and horror. By eliminating the hues, the visual potency is firmly controlled with an unusually protracted quality. Our commitment to this process ensured sharp charcoal images. The sight of Errol’s malignant swelling has also been condensed into cerebral horror, rather than merely an object of fleshy revulsion.

For instance, our first look inside of Darlene’s office first looks ominous and shadowy with subdued light, as she is deep in thought after the rejection. When she presses a stethoscope onto Errol’s back, it looks more canvas-like in the light, which makes the room look more like a cave-dwelling. The sound of a dripping faucet emphasizes this. The sound of the patient’s breathing transitions from external into Darlene’s head as what she hears from the stethoscope becomes more pronounced, silencing everything else that is outside. Then we see her framed medical degree. How she wishes it instead framed a work of art she could call her masterpiece.

Even the following scene looks more like a office rendered in film noir as Darlene reviews Errol’s file. The room looks more like it belongs to a corrupt mobster with Mindy the henchwench waiting for instructions. It is only when Errol enters Darlene’s office for the first time that it looks closer to what you’d imagine a doctor’s office looking like on an average day. As for Errol’s next horrendous visit, the room with the lights off save for a drafting light cast a sharp darkness as though either character could walk into the blackness and get lost in the void.

The seasonal shifts in the doctor’s office energize the picture, giving the scenes variety in tone and feel. For summer, the lobby looks hot and grubby, especially as Darlene awaits Errol’s judgment. The natural world is present at first, however, the following scenes eliminate that in favour of walls, glass and steel. For autumn, the effect of an afternoon sun hanging low gives the lighting a harsh brightness on the foreground of Darlene and Mindy from behind the front desk. This is in contrast to the hallway behind them, which looks dark and muted, creating a warm-coldness. For Christmas, the room looks overcast with dark shadows, while the Christmas lights come across as feeble attempts for spreading good cheer.

Finally, once Errol rides the elevator up in a shot depicting the back of his head on his last day alive, like Darlene and her stethoscope, the diegetic sounds of the running elevator transforms into a very subtle track of gears and faraway wails as heard by Errol. The sounds become more intimate with Errol’s private hell as ominous thumps express the terrible headache that he suffers from the tumor. We snap out of this as the elevator door opens and follow him into the lobby. Here it is revealed that there is no sunlight coming through the windows. It is so late on a winter day that it looks like night, leaving the clinic suspended in darkness.

The ambiance subconsciously fuels Darlene’s tension. Every breath, cough and sniffle carries the promise of infection. The doctor’s waiting room must feel utterly contaminated. Like Darlene, the movie is very sensitive to sound. In the most hushed dramatic sequences, the light breathing and heartbeats make it sound as though we live in a stethoscope. The soundtrack is a counter-balance between unnerving silence and ominous invention. The provocative music by James R. Kim transitions from chill-inducing instruments to raging punk.

The dramatic performances are tantamount in adjacent to the camera capturing them in the examination room that looks familiar, yet oddly peculiar. It is an early indicator for the audience as the movie transforms from being cold, clinical and studied into a more dynamic and primal vision. As Darlene and Errol transform into sweeping figures with their long coats and exaggerated features, their inner humanity is vividly recorded like they are under a microscope.

The shooting and editing of the final confrontation values coherence and steady movements so the action is undeniable. The violence is captured with visual wit, using slight-of-hand for the most brutal bodily transgressions. It is important that the violence feels shocking and dangerous. The most disquieting moment may be the cold, mechanical-like montage of forensics photos depicting the bloodbath in gritty, saturated color. It is jarring like a breaking news bulletin interrupting the black-and-white nightmare.

I am very passionate about creating genuinely dark and thought-provoking movies. It is a worthwhile challenge to make troubling subject matter perversely enjoyable while preserving its disturbing nature.

The artistic process is often supplanted with positive traits; however, I think that the worst aspects of human nature, like anger and sadism are just as integral and instinctual sources for inspiration. I believe a truly transgressive work of art can shake people out of their complacency and make them really think about how we treat one another.

The best horror movies act as cathartic vessels to channel our deepest fears and exorcise our inner demons.

One of my favourite contradictions about Socket is that the tone and narrative appears nihilistic, yet all its characters are relatable in their less admirable moments. It takes a great deal of compassion and insight to depict strong characters who succumb to their weakness and loss without making them “learn a lesson”.

This deeply unsettling movie would be best described as a comedy of manners. My aim is to subvert how the audience relates to the characters to make them engage with their own dark nature. It is my hope that Socket will rock people to their core.

Christopher Beaubien’s knowledge for the movies has made him a walking encyclopedia of all things cinematic.

Before entering the School of Motion Picture Arts (MOPA), he successfully completed the IDEA (Illustrated/Design: Elements and Application) program. It solidified his background in graphic design, and led to many interesting projects such as illustrating a children’s book, and designing props, namely a poster for Back to the Future’s Lea Thompson to look at.

His production company, CINELATION, is a labour of love. Essays on various films garnered the attention of fellow reviewers as well as the producers of Synchedoche, New York (2008) led to an invitation to participate in a Critics’ Round Table discussion of the film in New York City. This was included in the DVD’s Special Features section.

He has recently graduated with a Bachelor’s Degree studying filmmaking at Capilano University. His latest short movie Siren (2020), a psychological thriller, is complete and been screened in over sixty film festivals including the Hard:Line International Film Festival, which prizes “unusual story-telling methods (and) an exotic visual language… that could be important in the future of the genre.”

FILMOGRAPHY

Paperclip Love (2013), Bridge No. 29 (2014), Burn Beautifully (2014), Socket (2016) and Siren (2020)

CAST AND CREW

David Cutcher … Errol Cloutier

Amelia Morris … Mindy Harlow

Evelyn Clarke … Elle Riley

Julianna Franchini … Medical Assistant

Melissa Plisic … Police Officer 1

Matt Seeley … Police Officer 2

Rachelle Younie… Paramedic 1

Brie Dunphy … Paramedic 2

Christopher Beaubien … Detective 1

Chris Wilton … Detective 2

Peter Warkentin … Forensics Expert

Jared Cloutier … Runaway Patient

CLICK TO SEE MORE OF THE CREW The GenreBlast Film Festival 2018 Nominated for The Rio Grind Film Festival 2016 Vancouver Badass Film Festival COMING SOON SOCKET (2016) Is Going to Cinema New York City! My New Short Movie SOCKET (2016) Premieres in Vancouver at the Rio Grind Film Festival!

Hilary Muth

Taylor Wilson

Victoria Walsh

Matt Seeley

SOUND EFFECTS / AMBIENCE EDITOR

MAIN TITLE / END CREDITS DESIGNER

ADR RECORDIST / FOLEY ENGINEER

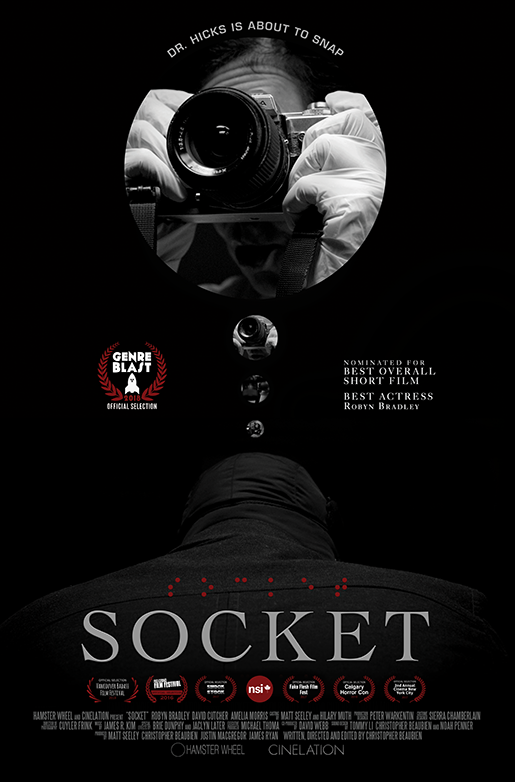

FILM FESTIVALS

Best Overall Short Film

Best Actress (Short) – Robyn Bradley

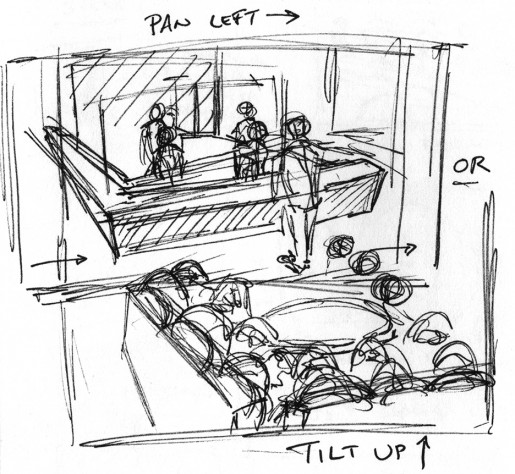

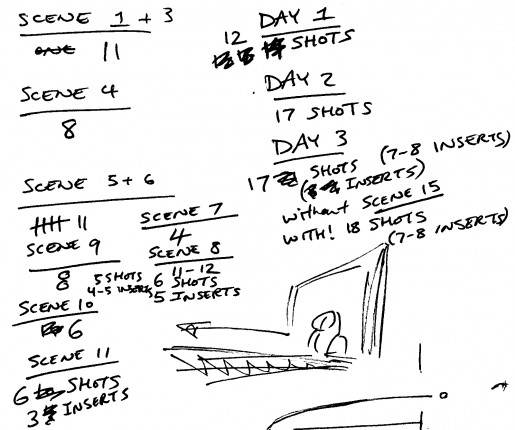

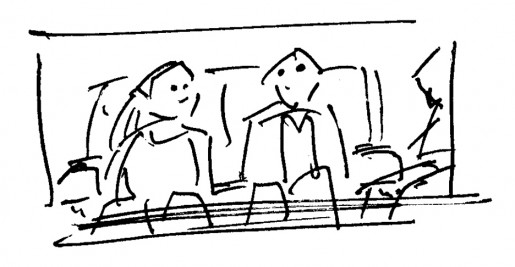

CONCEPT ART

UPDATES

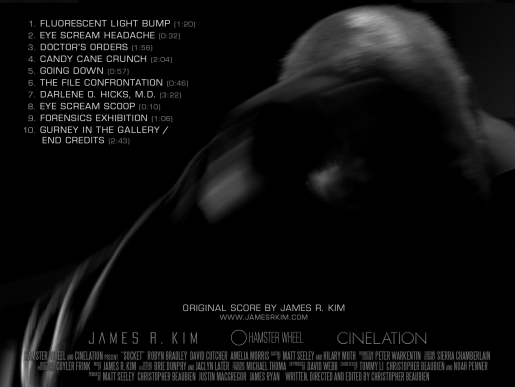

SOCKET (ORIGINAL MOTION PICTURE SOUNDTRACK)

by James R. Kim